The palladium price has hit a new record high in recent days over $1,700/oz, and the FT has declared there’s more to come unless we see a global recession or substitution of much cheaper platinum. I agree. And yet at present not only is there no evidence of substitution but there’s evidence that there has been no substitution.

It comes from North Macedonia.

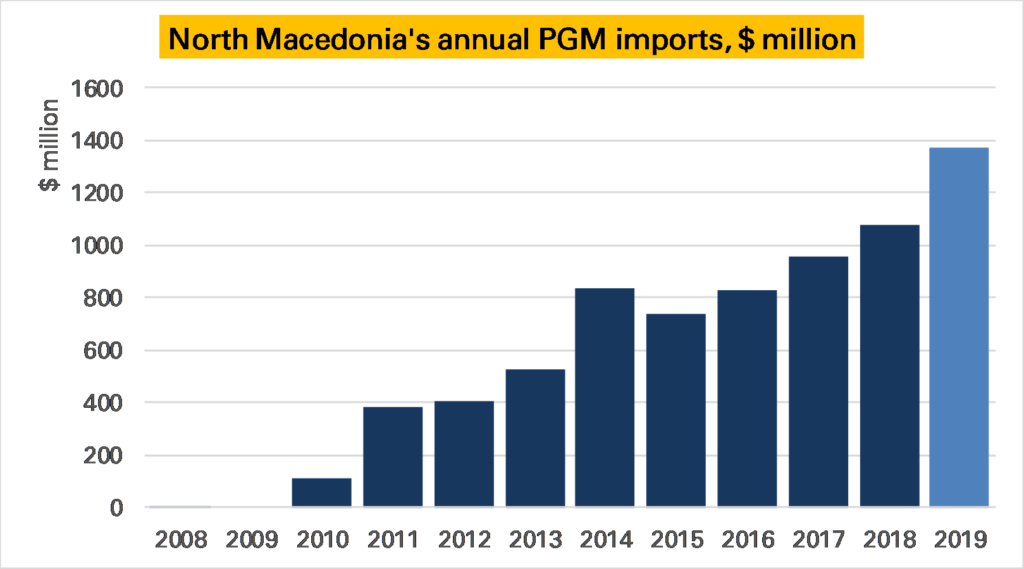

This country had little to do with the global PGM markets for much of its history. It is not a producer, and in 2009 reported imports of unwrought PGMs of only $1. That might sound a little implausible, but probably not far from correct – in 2008 PGM imports were less than $20,000.

And yet in 2010 it imported over $100m of PGMs. And by 2018 this was over $1bn, with more than 1 Moz of PGMs imported. This year is approaching $1.5bn.

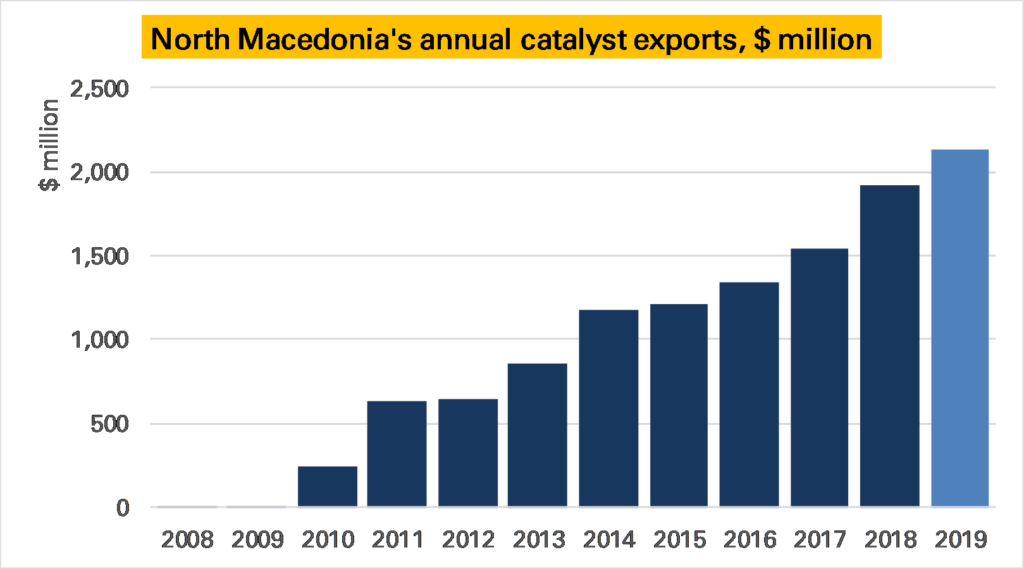

What gives? In 2010 refiner Johnson Matthey (JM) opened a diesel autocatalyst plant, which was expanded in 2013. This is why North Macedonia’s exports of catalysts also exploded, rising from nothing in 2008/2009 to nearly $2bn in 2018 (Macedonia has not gone its own car industry).

This is great for an analyst. Other large catalyst manufacturing countries are also PGM traders, such as the UK, and/or jewellery consumers, such as the China and the USA. This means it is hard to draw firm conclusions from trade data. But in North Macedonia it is just catalysts – therefore it is safe to assume the imported PGMs are being used in that sector.

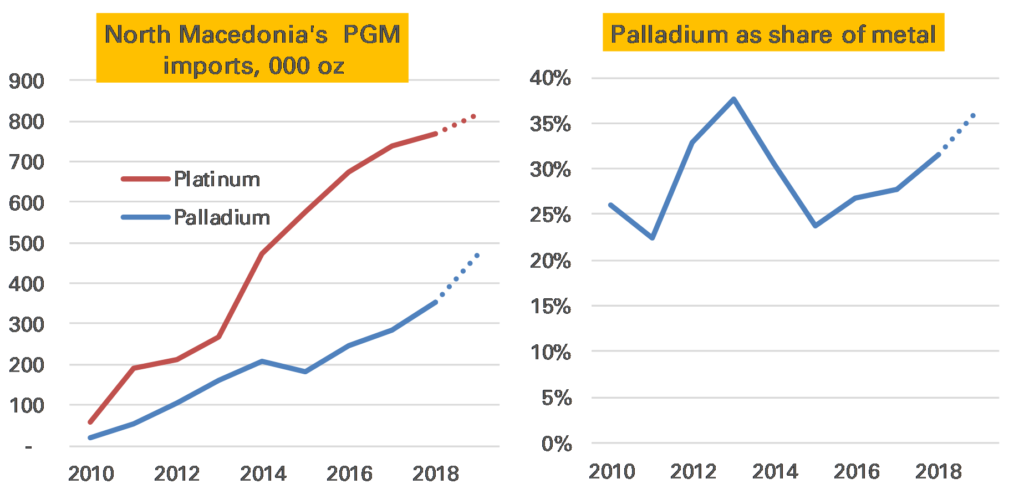

As such because we can break the trade data out by metal we can use it to estimate what proportions of platinum and palladium JM are putting in their catalysts. If we look at its imports by volume, we see that more platinum is imported than palladium – in 2018 nearly 800 koz of the former to around 350 koz of the latter – making palladium 28% of the combined volume to platinum’s 72%. This is to be expected given the plant is producing diesel catalysts. But importantly this proportion of palladium in the mix doesn’t seem to have fallen in the last few years – indeed it modestly rose from 24% in 2015*.

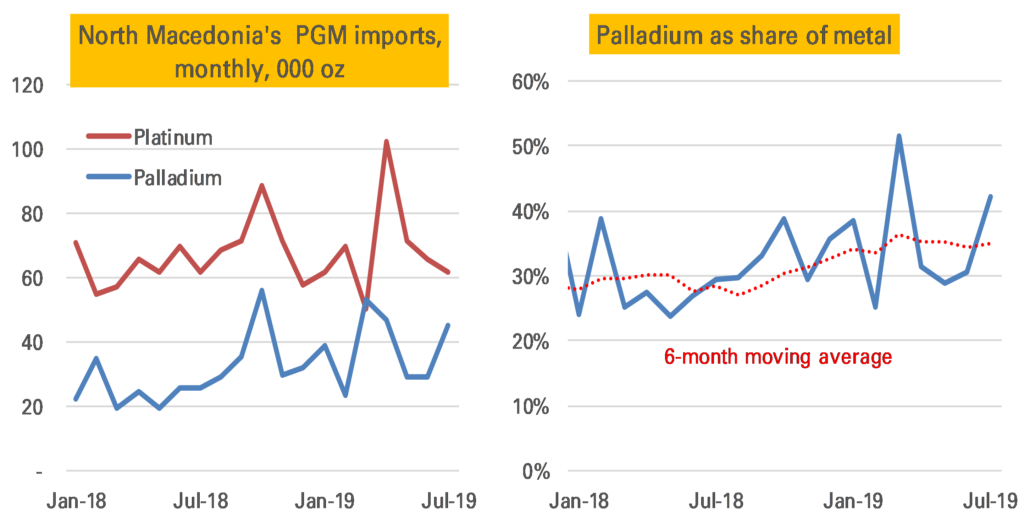

Perhaps the shift has only happened in the last few months? Not that either. Indeed while monthly import data is quite volatile, if there is a clear trend it is the other way, with palladium seeing a share of 50% in one month.

This data can’t prove no substitution is taking place. There could be other effects masking it, for example if JM have been importing additional palladium than they are using in catalysts (indeed it looks likely), perhaps ahead of the rising price or Brexit. It also might be that the mix of heavy and light vehicle autocatalyst could have changed, affecting the ratio (that’s what seems to have driven palladium’s share down in 2013 after the plant’s first expansion). And if the plant had begun manufacturing gasoline catalysts all bets would be off, though then we would also see rhodium imports, and we have not.

We also can’t assume that JM’s Macedonia plant is representative of all their catalyst plants or those of other catalyst manufacturers. And it is possible substitution is happening in gasoline catalysts, not diesel ones.

Nevertheless it is strong evidence that there has been no substitution. After all most analysts believe if substitution is to come it would come first in diesel, where car and catalyst makers are most comfortable with using platinum.

The palladium price could be going higher yet.