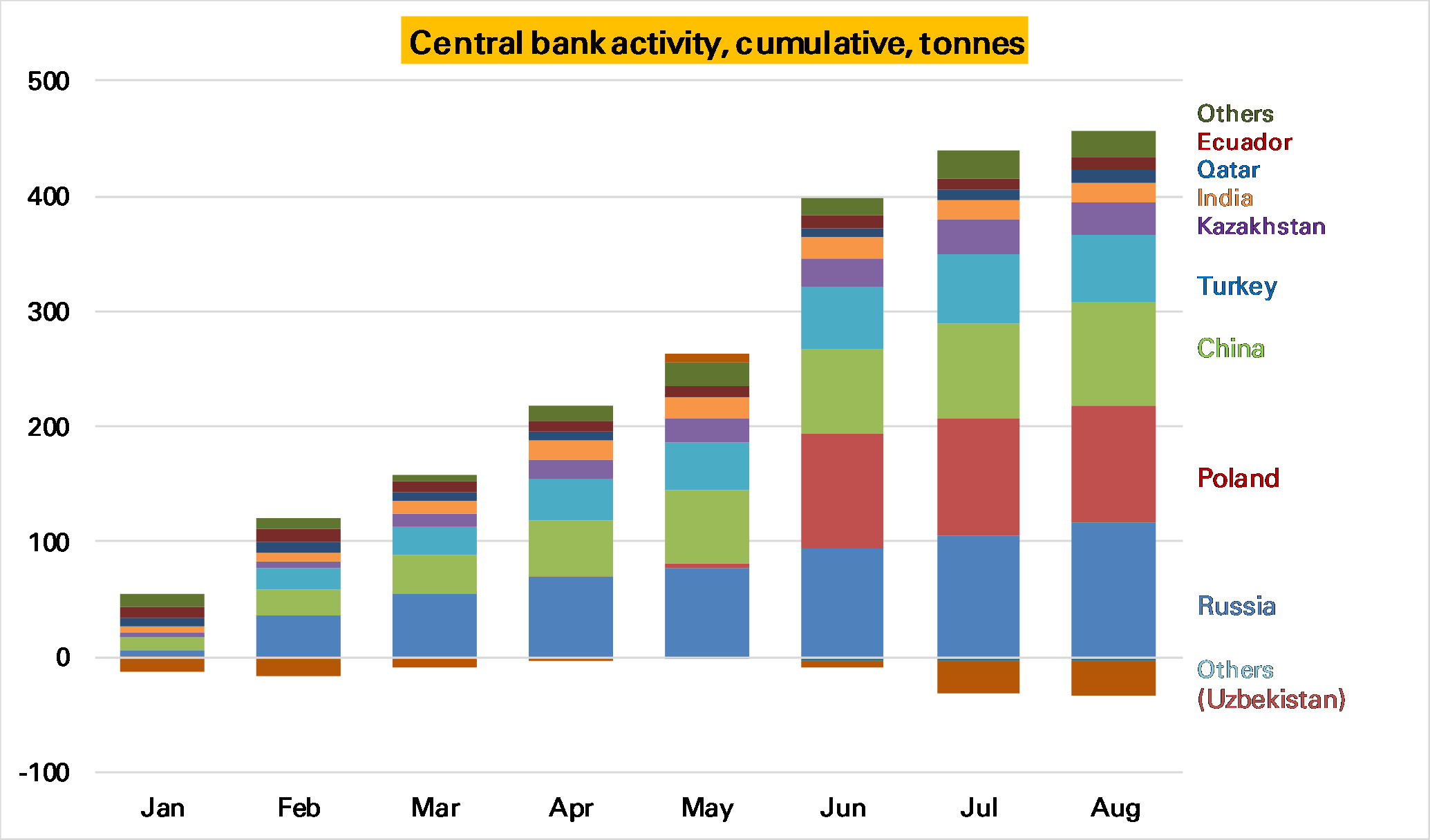

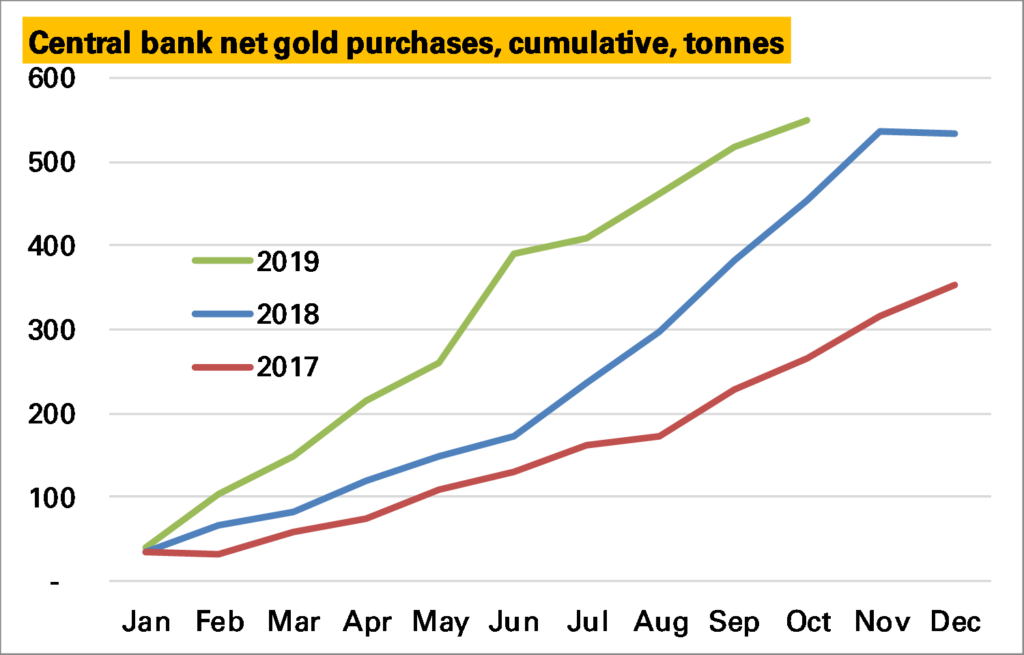

If faltering jewellery demand is a a reason to be concerned about the strength of the underlying gold market, central bank buying has been a clear positive, with 2019 set to be another record year for net purchases.

As of October, the latest available data for most countries, there has been a net addition of 550 tonnes to central bank reserves, 17t more than in the whole of 2018 and far ahead of the amount seen in 2017.

Purchases are slowing, however. By the end of the first half of 2019 net purchases had already reached 390t, an average of 65t/month. In the last four months 160t have been purchased, a slower 40t/month. This figure might rise a little – some countries report late, and the trend tends to be higher – but is unlikely to change much.

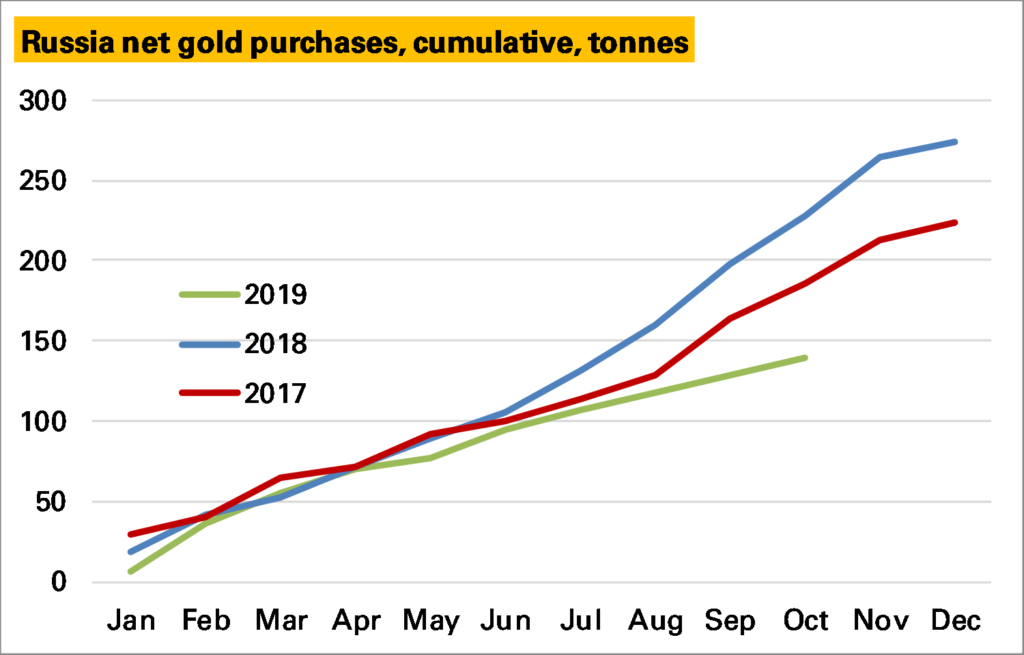

To what extent is this a concern? A key reason for the H2 slowdown is Russia, the bedrock of global central bank gold accumulation. Here purchases in 1H were broadly inline with previous years, but since then have been much more muted. This is in line with a new policy adopted by the Central Bank of Russia to reduce gold accumulation and has meant an increased rate of Russian gold exports. As such it looks set to be a drag on the global total going forward, albeit one that was inevitable at some point.

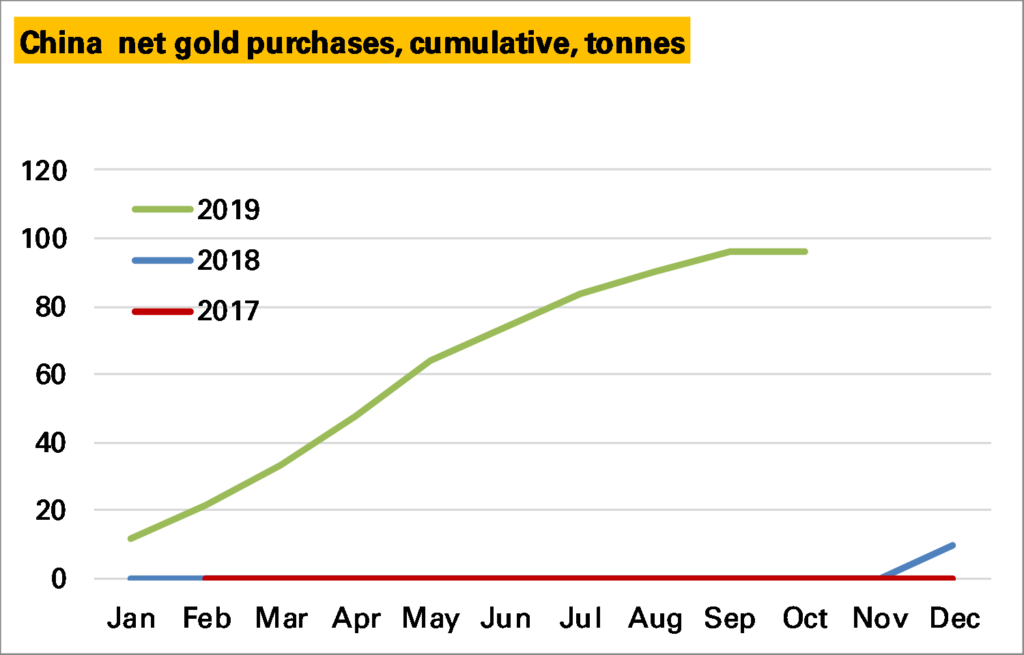

Also helping purchases in 1H 2019 was a resumption in Chinese central bank gold buying after a few years hiatus. This too seems to have slowed a bit in 2H but it is too soon to know whether October’s zero purchases marks another cessation of buying or is a temporary pause.

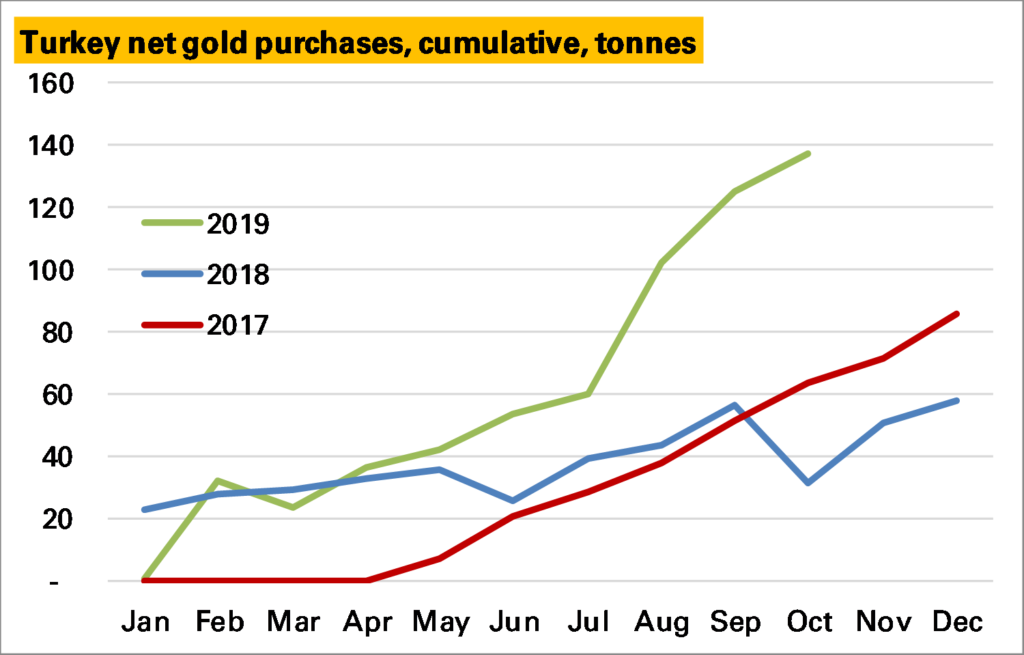

What has prevented an even more rapid slowdown, however, has been an acceleration in purchases from Turkey – on nearly 140t YTD, far higher than in previous years. Whether this will continue is a difficult one to call. Turkey’s central bank gold policy is somewhat confusing given they also hold private-sector gold against reserve requirements (these numbers exclude that), but there has been a policy shift in favour of gold in recent years.

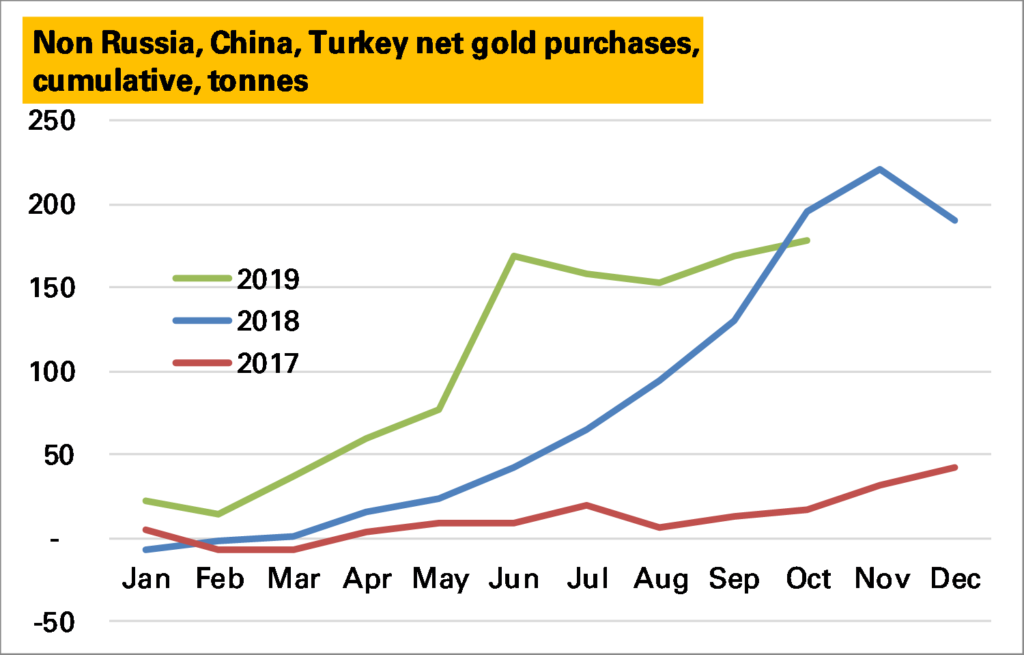

Finally, there is the Rest. And in recent years these have been the great hope of the gold market with a number of big purchases, particular in Europe from Hungary and most impressively Poland. In 1H 2019 other countries added 160t of gold, far more than ever before. In 2H so far barely 10t have been added. However the nature of these purchases mean that they tend to be lumpy.

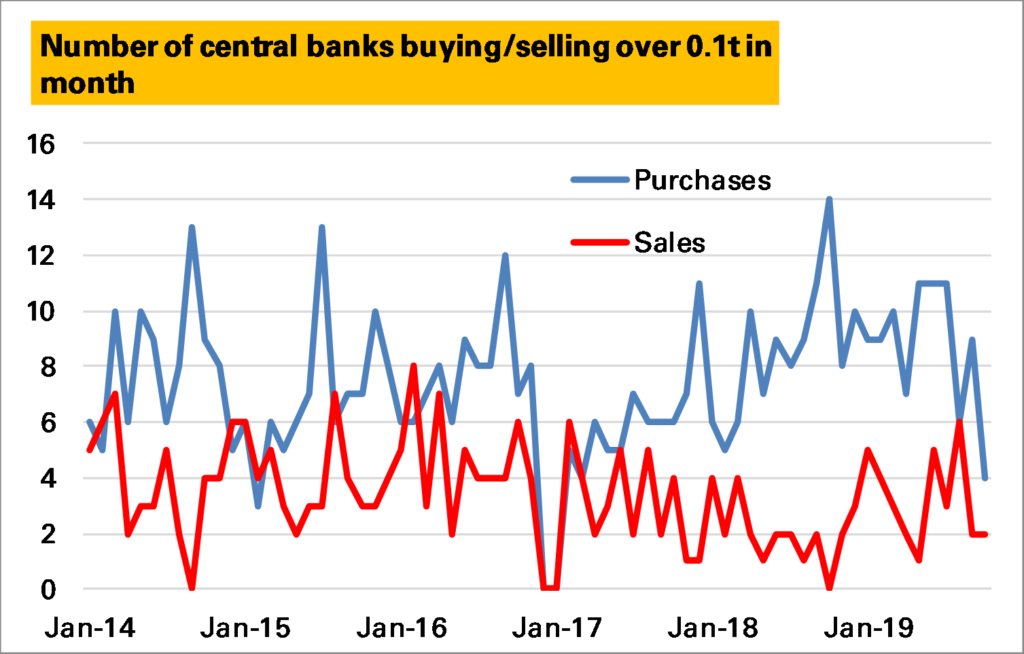

Indeed if we look at central bank activity, here shown as the number of central banks buying or selling in a month, we see an increase through 2018 in purchases, and a decline in sales, which has since reversed (note I’m excluding the BIS here, correctly, and Turkey, incorrectly, which in most months would add 1 to the purchases line).

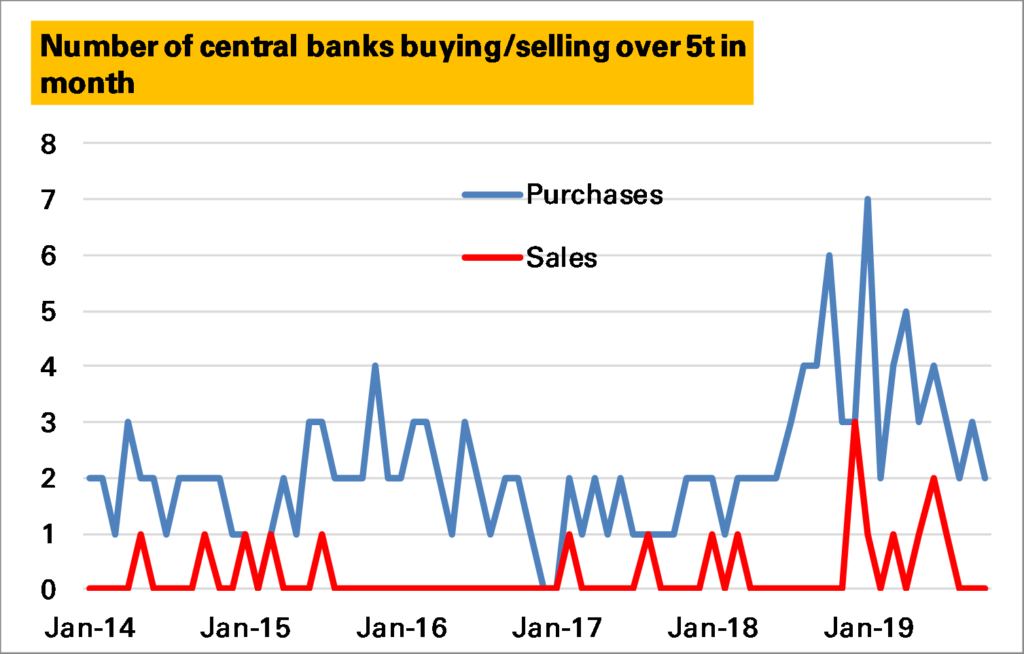

If we choose a less granular measure, say 5t/month, the trend is even clearer (note exceptions above).

So it does look as if there has been a slowdown in central bank buying, and not just because of Russia, which is the biggest impact. One explanation could be the high price, which might make the case for switching into gold harder to explain. But its worth remembering that the pace of buying in 1H 2019 was unprecedented, and current rates are still quite positive. The main concern I have is that Turkey is unlikely to be as reliable a buyer as Russia.

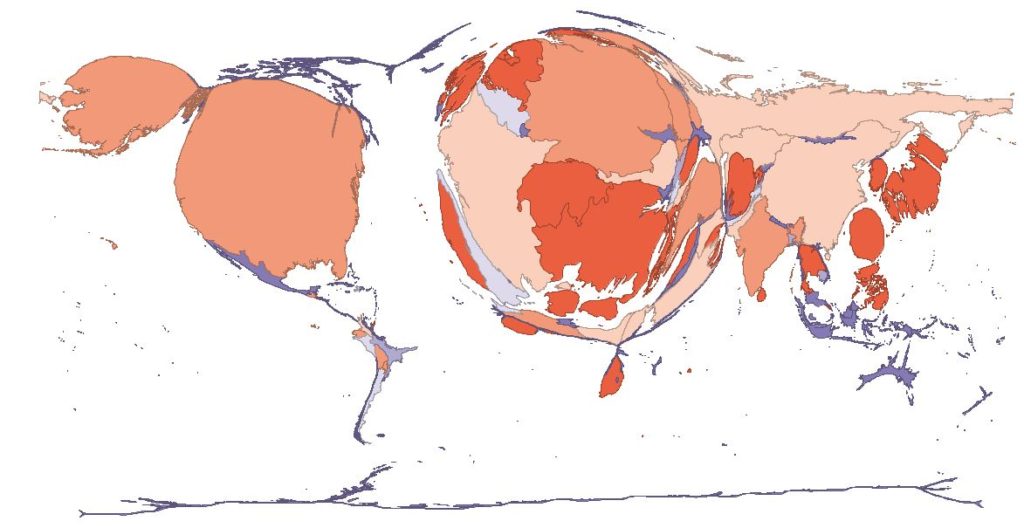

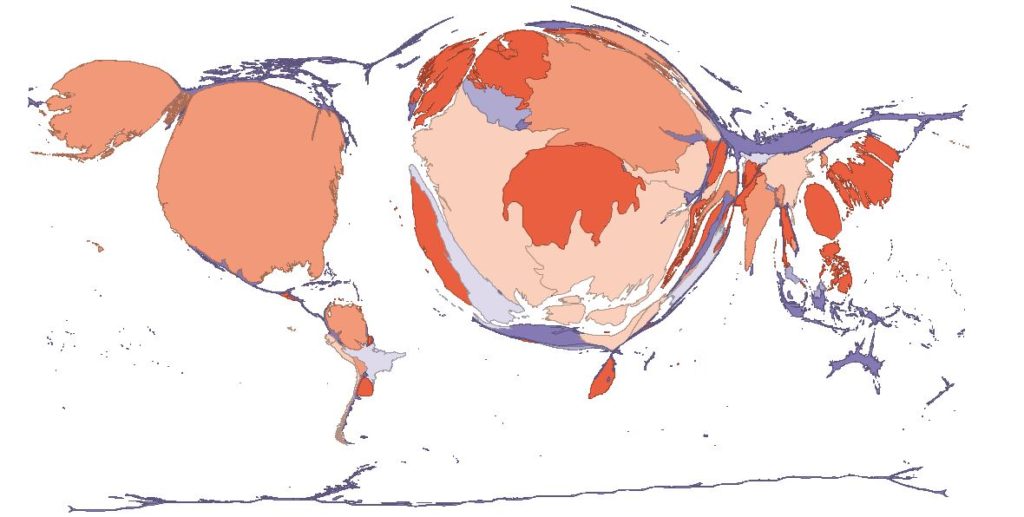

Over time this remains a positive part of the market, and I expect central bank purchases to continue, not least because of the imbalance in global holdings shown here (each country is resized to reflect the size of its gold holdings). For more details see here.